Something’s rotten in the global supply chain—figuratively and literally, as Shanghai’s Dragon TV revealed in July about a major supplier of meat for the iconic restaurant brands KFC, Pizza Hut and McDonald’s. In recent years various supply chains brought to market, through respected public companies, adulterated products such as drug-infused toxic chickens and horsemeat posing as beef, as well as dangerous products such as salmonella-laced peanut butter and melamine-fortified pet food.

In addition to the restaurant, food retail and agribusiness sectors, problems originating in their supply chains have adversely affected the automotive, electronics, pharmaceutical and toy sectors. GM, for example, is now dealing with what appears to be a 10-year long supply chain problem that compromised product safety. The immediate costs of all this supply chain rot may include business interruption, product recalls and third-party liability claims, but strategic costs may extend to reputational harm, too. With the rise of investor activism, the worst recent additional costs may be the personal reputations of corporate directors and officers.

Three reasons explain the rising costs of supply chain issues. Stakeholders expect that companies know how the products they offer are made, by whom, and with what raw materials. These expectations are not limited to “conscientious capitalists” or NGOs. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, for example, requires companies to disclose annually how they test for whether any minerals originating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or an adjoining country are incorporated in products.

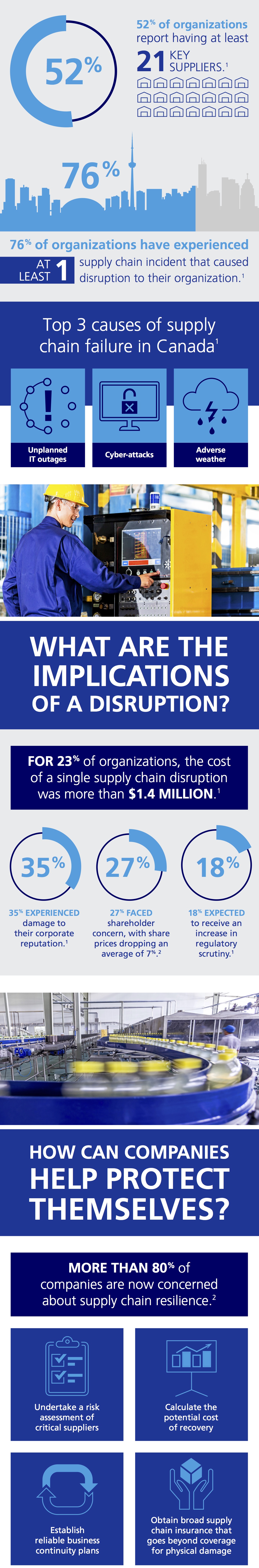

Another fact is that, as companies continue to grow around the world in an increasingly complex sourcing, manufacturing and distribution environment, insurers and their reinsurers are balking at accepting risk. A representative of Zurich, a major insurer of the global supply chain, explained that reinsurers were demanding more transparency into locations as a going-forward condition for blanket limits.

Then, intolerance for errors is growing. Stakeholders, many of whom now have near-instant awareness of errors and a front-row seat to global crises, are becoming less forgiving of companies being blindsided.

Only a short window of time now separates an adverse event from the onset of what the Financial Times once described as “the pile on of litigators, regulators, and…bloggers.” Enter now also activist investors. Despite ample public contrition, Target’s board sacked its CEO only 18 weeks after a supplier provided credit card scanners whose security had been compromised—a sacking that did not prevent activist investors from calling for a sacking of the board. And only 10 weeks after Duke Energy’s coal ash spill and its public contrition, activist investors demanded the heads of four Duke Energy directors.

The court of public opinion where liability insurance offers no solace has become the primary battleground, making directors and officers especially vulnerable. One investor told the New York Times his opening gambit with the C-suite: “We can make you famous, and not for the reason you want to be famous.” Rarely will a company’s C-suite suffer public opprobrium silently like Rolls-Royce’s after a catastrophic engine failure exposed a systemic safety issue in their supply chain.

buy wellbutrin online https://galenapharm.com/pharmacy/wellbutrin.html no prescription

The company went radio silent for 10 weeks until it isolated and repaired the problem, whereupon the firm emerged publicly to announce a new large engine order. They used the third-party endorsement of a respected customer to help reassure stakeholders and restore their reputation.

It is high time that companies acquire visibility into their supply chains, and demand from them responsible behavior appropriate for the notably higher 21st century norms. They can begin by evaluating the effectiveness of field audits that evidence compliance. Although that approach is industry-standard, it is expensive and disruptive to their suppliers and expensive to administer. For the overwhelming majority of suppliers and vendors that are in compliance, these audits interfere with their operations and strain the supplier/company relationships. For the few that are non-compliant, infrequent audits are poor policing tools. When audits fail to uncover deviations, and a negative event occurs, social critics have unfairly accused companies of ineffective oversight and even willful failure.

New integrated information management solutions are far more effective. These will help companies find hints and clues of noncompliance in open communications that, aided by big data analytics, converge on apparent discrepancies between self-reporting and actual behaviors. These signatures of misbehavior will more quickly expose potential deviations from responsible behavior and enable corrective actions.

Companies can also reduce irresponsible behavior by making it harder for potentially deviant suppliers to rationalize such behavior and assuage their guilt. Insurances have become available that will objectively affirm the authenticity of a company’s values and neutralize rationalization that might lower the barriers to irresponsible behavior by some suppliers. Insurances can also increase the disincentives for irresponsible behavior in two fundamental ways. First, escalating the behavior into the criminal matter of insurance fraud is a far greater disincentive than a terminated contract. Second, by making insurance a condition of contracting, loss of insurance becomes an independent and non-judgmental basis for termination.

Companies cannot then be vilified for evading responsibility.

Companies that manage risks to their supply chains in a way that stakeholders can appreciate and value can transform risk management into a strategic advantage. These companies will emerge with reputations for being 21st century industry leaders in governance, management and control.