An estimated 26 pieces of a school bus-sized dead satellite are predicted to survive reentry into the earth’s atmosphere and have a good chance of crash landing somewhere on land (or sea) tomorrow.

But don’t take off for the nearest bunker just yet. NASA says the chances are 1 in 3,200 that someone somewhere will be hit and they have just now reported that the satellite will not hit the United States.

The latest predictions of the satellites re-entry mean that the U.S. will miss out on the stunning sight of the spacecraft as it re-enters the atmosphere. A NASA spokesman said: “Re-entry is expected sometime during the afternoon of Sept 23, Eastern Daylight Time. The satellite will not be passing over North America during that time period. It is still too early to predict the time and location of re-entry with any more certainty, but predictions will become more refined in the next 24 to 36 hours.”

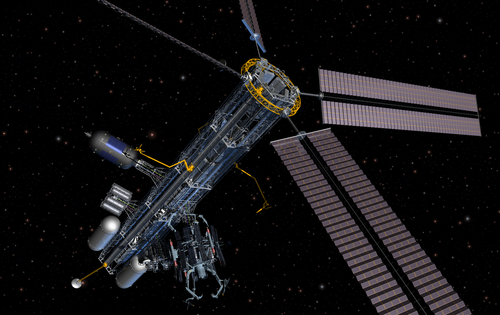

Launched from the Space Shuttle Discover on September 15, 1991, the Upper Atmospheric Research Satellite (UARS) was the first satellite dedicated to studying the science of the stratosphere. As Discovery News reports, this machine was a commendable satellite among the many space vessels.

The final demise of this bus-sized hero of atmospheric science is happening almost 20 years to the day after its launch. There were many other major discoveries over the years, of course. The project scientists have their own top ten list. But if you remember only two things about this NASA workhorse, let it be these:

- In its first two weeks of operation, UARS data confirmed scientists’ theories about ozone depletion over the polar regions by providing three-dimensional maps of ozone and chlorine monoxide near the South Pole during development of the 1991 ozone hole.

- UARS data provided conclusive evidence that chlorine in the atmosphere—originating from human-produced chlorofluorocarbons—is at the root of the ozone hole problem.

Impressive, indeed. So let us not focus solely on the hype surrounding its reentry tomorrow, but instead, focus on the accomplishments this man-made space scientist achieved during its career thousands of miles above us.

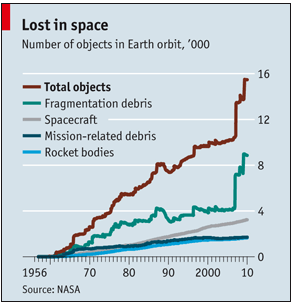

With lucky timing on our part, we covered the issue of space debris in our October issue. Within our Timeline column on the topic, we covered everything from the first warning of the dangers of space debris back in 1978, to the recent National Research Council report, saying the issue is at a “tipping point.” Check out the Risk Management site on October 1st to read the article its entirety.

Do you have insurance coverage for this type of event?