As COVID-19 vaccines are rolled out around the world, effective risk management coupled with predictive analytics can help ensure supply chain stability to quickly and safely deliver them. Pharmaceutical companies and stakeholders around the world are scaling their vaccine roll-out, and concerns are emerging around logistical challenges of how to manage quick global distribution. One thing is clear: the entire supply chain’s stability needs to be monitored carefully, as a single fracture can have catastrophic effects on distribution of this time-sensitive vaccine.

Pfizer has designed an innovative logistical method to control vaccine distribution from manufacturing to local cold-storage facility. Much has been written about vaccine producers’ heroic efforts to secure upstream components such as glass vials, stoppers, and crucial vaccine ingredients, as well as the distribution packaging, including dry ice capacity, specially manufactured cold-boxes for vials, airfreight logistics and more. But very little has been reported on the downstream, or on-the-ground distribution of the vaccines around the world. As the vaccine touches down in states across the United States and countries around the world, the real distribution challenges begin.

As in every industry, risk originates in many places along the supply chain. Geopolitical risk, fraud, and third-party financial risk all must be understood if the vaccine is to reach the greatest number of people in the shortest amount of time. While some believe responsibility for distribution lies solely with individual localities, they are forgetting that the entire supply chain and logistics industry has a moral imperative to ensure that the vaccine is properly and fairly distributed.

Even with the best planning, plenty can go wrong, including:

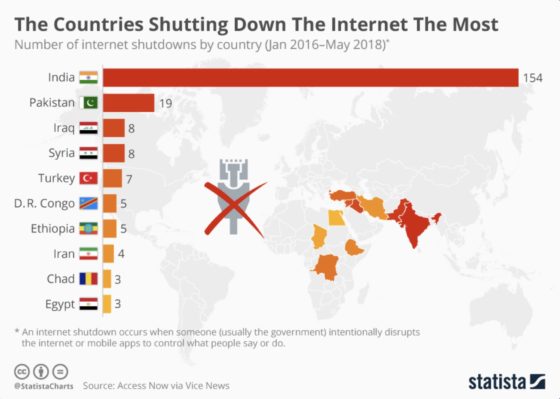

Geopolitical Risk: If history has taught us anything, it is that some in power will manipulate the distribution of life-saving relief to their political advantage. Examples include the United Kingdom’s blockades of food to Ireland and India, Sierra Leone military juntas interfering with United Nations food relief, and Somali intelligence officers kidnapping the World Food Program’s local chief, among others. Closer to home, President Donald Trump tried to manipulate the distribution of PPE away from states that did not support his politics. Once life-saving vaccines arrive in local facilities, it will be a monumental task to distribute them fairly, and in a manner that does not give more power to local officials who seek to use them to further entrench corruption.

Financial Risk: Many organizations can stumble while rolling out distribution programs. Without proper chains of custody, fast financing, and quick due-diligence on third-party logistics suppliers, even the most well-oiled machines could fail to deliver the vaccine in a successful manner. The scale of vaccine demand is massive. Shortages are already present for raw inputs, and for critical infrastructure components. To meet these unique challenges, access to fair financing and payments should be guaranteed to all participants in the supply chain (i.e. no 90-day contracts for truck drivers who are moving the vaccines.)

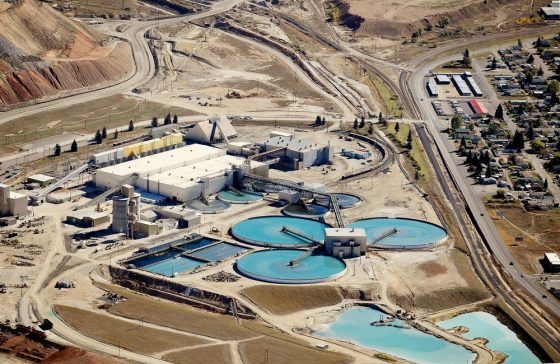

Geolocation: Risks like natural and manmade disasters, lack of last-mile distribution, and poor infrastructure can all cause a single point of failure. The technology exists to ensure that vaccines are sent to the most geographically ideal local distribution hubs, and predictive forecasting should be employed to ensure the most timely deliveries.

Since risk can originate anywhere along the supply chain, everyone involved in the logistical aspect of vaccine storage and distribution needs to assess the existing systems to calculate and correlate risk. Leveraging technology is the best way to gain visibility. Rather than rely on gut instincts to determine supplier and partner risk, those in charge should use data to make decisions and consider implementing automated intelligence technology to actively predict and correlate how a change in geopolitical risk will affect the financial health of suppliers. Proactive planning is not only crucial for continuing rollout of vaccines for the current pandemic, it is also paramount in being prepared for the next pandemic.