The storm that destroyed large swaths of Oklahoma was unfathomably destructive. It’s vast size was frightening, its energy enormous, its tragedy permanently unforgettable. Even with all the tornadoes to ravage the U.S. landscape in recent years, this one is uniquely disturbing. The images of flattened neighborhoods full of shattered-toothpick homes and mangled cars look make believe.

With at least 24 dead and more than 200 injured, the human toll has been massive.

In this video, Moore, Oklahoma, Mayor Glenn Lewis discusses the devastation.

Though difficult, the future of preparing for tornadoes means looking beyond the immediate recovery and tragedy. It means looking for lessons learned and ways to better understand the threat.

Many media outlets are asking the right questions.

Foreign Policy, for example, asked “Why does the U.S. have so many more tornadoes than other countries?” The short answer: It “stems from a mix of climatological, topographical, and geographic factors.”

Such factors mean that the United States averages more than 1,000 reported tornadoes per year while the next-most-hit nation, Canada, only suffers from around 100 reported tornadoes per year. The Wall Street Journal’s contributing meteorologist, Eric Holthaus, broke down some of the weather-reasons that tornadoes occur.

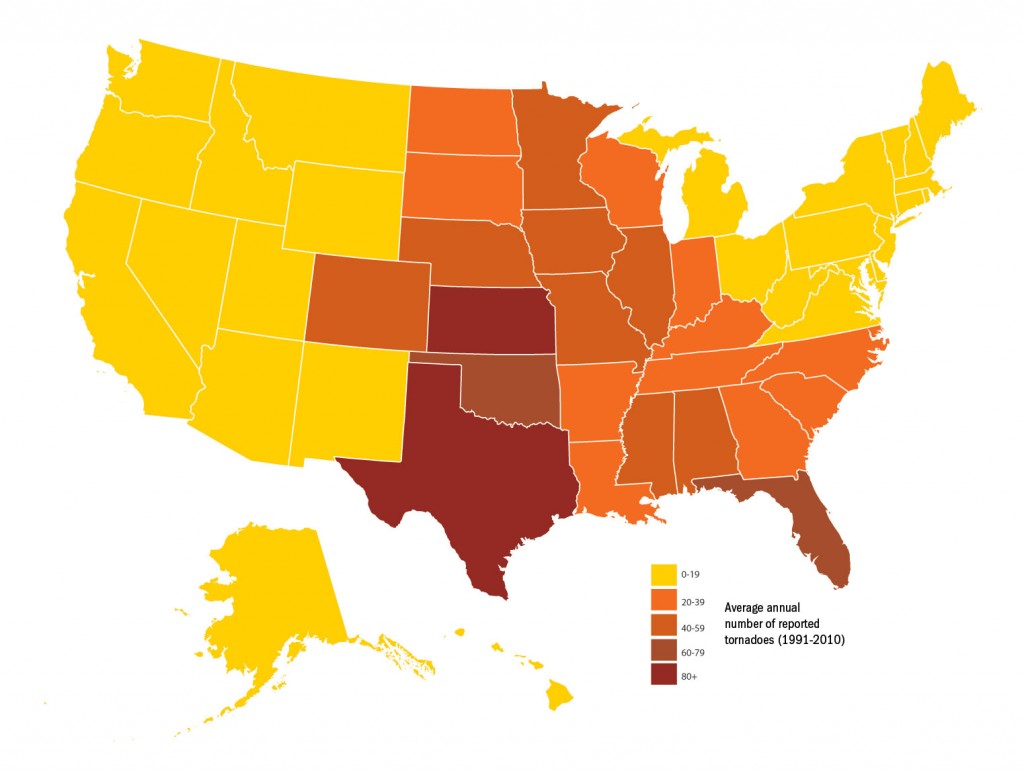

And here is a graphic, from the May issue of Risk Management, that shows where they occur in the United States. The so-called “Tornado Alley.”

(click for larger map)

While the United States’ predisposition to be stuck by tornadoes isn’t questioned by climatologists, a key word is “reported.” In some ways, our ability to understand tornadoes falls behind other natural disasters (namely hurricanes and earthquakes) due to the fact that we still can’t accurately know exactly when or how many tornadoes occur each year. They can be rapidly forming and dissipating funnels of wind, so unless there is someone nearby to witness them or human-made structures to be affected, some go unreported.

Given the progression of development and technology, that is much less so the case in 2013 than it was in 1950. But it is still a factor in our collective ignorance.

For example, the number of reported tornadoes in the United States has risen rapidly over the past 60 years. Some have tried to tie this increase to weather trends or climate change.

But the fact that more are being reported doesn’t necessarily mean more are occurring.

I wrote on the topic for the May issue of Risk Management.

Even in the United States — by far the world’s most frequent victim of twisters — detailed records only go back to 1950. Since then, there has been an average increase of 14 reported tornadoes per year. But any attempt to tie the rise to the weather would be an exercise in analyzing guesswork. Most experts believe this rise is due to advances in science, technology and observational techniques — not to mention the number of homes and businesses that are hit — rather than any objective trend that proves more tornadoes are occurring.

Really, nobody knows — now or then — how many tornadoes occur each year. “Socio-economic factors provide a better explanation for this trend than meteorological ones,” states a report by Lloyd’s of London.

Those who lost loved ones during 2011, a record-setting year for twisters, are unlikely to take solace in this fact. But “despite the anomalous 2011 season,” says the Lloyd’s report, “there is no trend in the number of strong to violent tornadoes between 1950 and 2012.”

In addition to the challenge of knowing how many tornadoes occur, there is the difficulty of predicting when and where they will occur.

The Washington Post‘s Wonkblog, is asking “Why are tornadoes so hard to predict?”

The short answer, from Carbin of the National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center:

“There are so many mild adjustments, slight adjustments that can make a huge difference in whether you end up getting the formation of storms. The sensitivity the atmosphere has to ingredients in the formation of tornados and magnifying that slight change in something we can’t even observe can have a dramatic impact on the forecast.”

Still, despite the limitations, things are improving.

It may not sound like significant progress, but even minutes saves lives.

Just 16 minutes before a gigantic twister first developed near Oklahoma City on Monday, the National Weather Service put out a tornado warning.

The tornado warning issued for the region south of Oklahoma City on Monday, May 20, at 2:46 p.m. (Via Mike Smith)

That doesn’t sound like very much time to get out of the way. For many, it wasn’t: At least 24 people died when the tornado ripped a mile-wide path through the city of Moore, Okla.

But those 16 minutes actually represent an enormous advance for weather science. Back in the 1980s, the average tornado lead time was a scant five minutes. Today, it’s about 13 minutes.

What’s more, meteorologists are now able to issue alerts and storm forecasts even earlier, thanks to powerful computers that allow them to run detailed weather simulations. The Oklahoma City area had been identified as an at-risk area days before the twister actually struck. And the National Weather Service’s Rick Smith issued an eerily prescient forecast at 11:30 a.m. Monday, alerting people to the threat of tornadoes that very afternoon.

Just how much more improvement is possible?

Carbin told the Washington Post that “we might be able to get, say, an hour lead-time on a tornado.”

That time frame, as a goal, sounds depressing. It’s certainly going to make tornadoes forever more difficult to prepare for than, say, hurricanes. But then again, it is a lot better than, say, earthquakes, which generally give zero seconds of notice.

As discussed on Wonk Blog, the world has also gotten better at understanding tornado behavior once a storm forms and is detected. This also adds time for those who might be in a twister’s path in a half an hour as opposed to those who reside near its formation.

A journalist from Arkansas I spoke with yesterday also noted another benefit of being able to better predict where a tornado is headed. Historically, throughout many areas of the South and Midwest, tornado sirens and warnings would be issued for very-large areas. Two whole counties perhaps.

This makes sense. Precaution is obviously the best strategy.

But it also has breed complacency. Some locations face many tornado warnings every year, and if multiple “DEFCON Ones” are declared that never present real threats, people naturally start to take safety for granted. The Boy Who Cried Wolf and all.

With better projections on trajectory and more-precise warning systems, however, sirens only have to be sounded for those who are actually at direct risk of the threat. Those who are likely to remain safe for the next two hours may not have to be told to hunker down in their basements. And in time this should lead to a population who comes to have better respect for the warnings of authorities.

Ultimately, this is all still very difficult science.

The truth is that as tragic as this tornado in Oklahoma has been, there will be more. 2011 was a historic year for twisters and the folks in Joplin, Mississippi, certainly share Moore’s pain. Even past residents of Moore feel the current residents of Moore’s anguish, as another devastating tornado ripped through the same community in 1999.

The hope, however, is that through knowledge, science, preparedness and resiliency, all citizens, municipalities and businesses will be more ready tomorrow than they are today for when the next tornado hits.

Hopefully, the next tragedy can be less tragic.

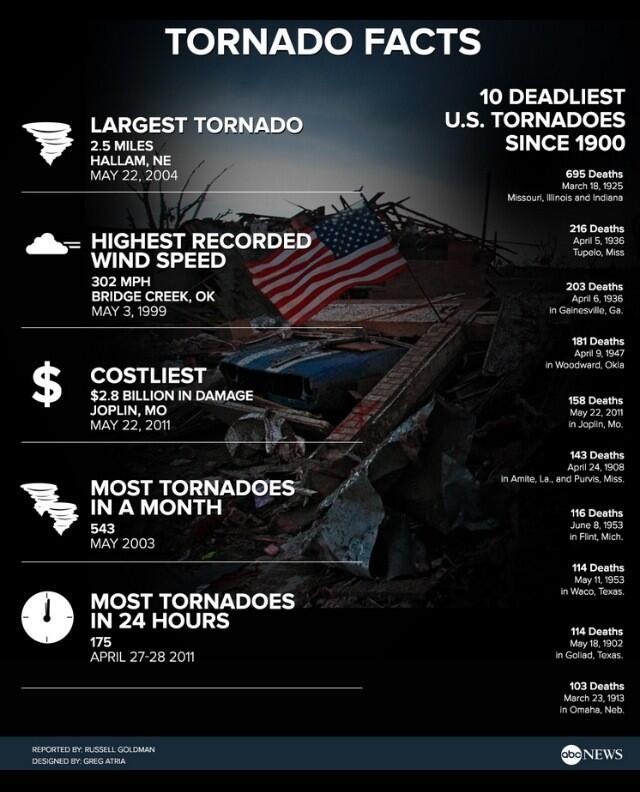

infographic via @Nightline