There are few issues as politically charged as water, not only because people’s survival depends on it, but also because it is a critical component of so many industries. Agriculture, food and beverage manufacturers, refineries, paper and pulp companies, electronics manufacturers, mining operations and power plants—are of these rely on a continuous and reliable water supply.

When companies move into markets with weak infrastructure or questionable rule of law, drawing on these resources can quickly bring them into conflict with local citizens and, sometimes, the host government. Because of its vital importance, however, water scarcity has become much more than a local issue for businesses.

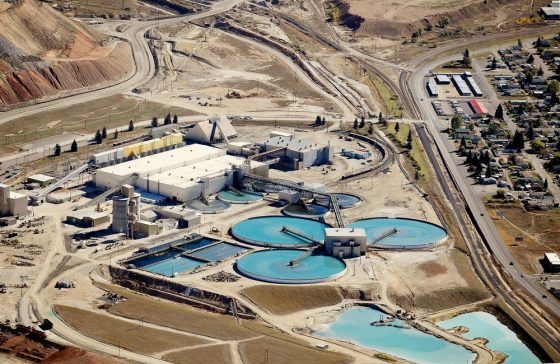

Water shortages can lead to conflict as competition grows for diminishing resources, as any scarce resource on which people depend is likely to become political at some point in time. One scenario that repeatedly unfolds is as follows: A mining operation depletes local water resources or has a tailings dam accident that contaminates a local river, a protest ensues and the host government intervenes in the project.

Hydroelectric power projects can create a number of similar political risks and some different ones, including relocation of local villages.

In recent years, however, awareness has grown about how water scarcity risk affects political risk at the national and international levels, requiring a different type of analysis.

The depletion of rivers, lakes and streams has led to more dependence on below-ground water. More than two-thirds of groundwater used around the world is for irrigating crops, and the rest of below-ground water is used to supply cities’ drinking water.

For centuries, below-ground water supplies served as a backup to carry regions and countries through droughts and warm winters that lacked enough snowmelt to replenish rivers and streams. Now, the world’s largest underground water reserves in Africa, Eurasia and the Americas are under stress, with many of them being drawn down at unsustainable rates. Nearly two billion people rely on groundwater that is considered under threat.

What makes the problem particularly difficult to solve in the emerging markets is that small, often subsistence, farmers are doing the drilling for water. The U.S. military called climate change, including reduced access to water, a “threat multiplier,” potentially threatening the stability of governments, increasing inter-state conflict, and contributing to extremist ideologies and terrorism.

It is always difficult to establish causality with something as complex as politics, but there certainly is circumstantial evidence that water scarcity was a factor in the Syrian uprisings that led to the country’s civil war. In Yemen, some hydrologists warn the country may be the first to actually run out of usable water within a decade, and combatants are making a bad situation even worse by using water and food as weapons against opposing villages. In Sudan, desertification and water scarcity have been cited as having a strong link to the Darfur conflict.

Since water does not respect political borders, the conflicts can become international. One of the most high-profile disputes has been Ethiopia’s damming of the Nile River for hydroelectric power, potentially threatening Egypt’s ancient water source. In 2013, Egypt’s then-president said he did not want war but he would not allow Egypt’s water supply to be endangered by the dam. Fortunately, in 2015, Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan signed an agreement allowing dam construction, provided that it did not cause “significant harm” to downstream countries. But the studies into how much harm it could do have not even been completed yet, and the dammed water could be diverted to uses other than power. Thus, the political risk surrounding the Nile River is far from over. Since 1975, Turkey’s construction of dams for irrigation and power have cut water flow into Syria by 40% and into Iraq by 80%, setting off disputes there.

Companies are accustomed to building water into their business plans in developing countries. Environmental impact assessments and proactive community relations programs can bring potential problems to the surface before they start, helping companies manage water in an environmentally and socially prudent manner. The geopolitical risks around water scarcity can be more difficult to manage, however. In this area, companies should consider building water scarcity into their political risk management and forecasting frameworks, factoring it in when making investment and supply chain decisions. If governments cannot find ways of sharing this limited resource, political violence risk may become even more of a factor for international businesses to consider.

This article previously appeared on Zurichna.com.