A strategic risk management (SRM) program is designed to assist organizations in identifying, prioritizing, and planning for the strategic risks that could impair or destroy businesses and reduces the chances of these kinds of crises. And while hindsight is 20-20, an SRM program – or a more effective one – could have helped Boeing avoid some of its recent high-profile crises.

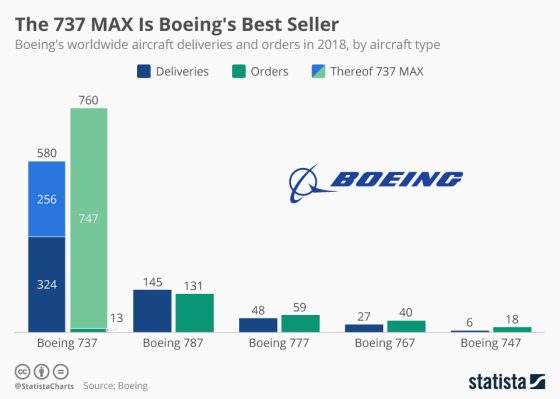

Between October 2018 and March 2019, two crashes involving the Boeing 300 737 MAX 8 models resulted in the loss of 346 lives. Since then, Boeing has:

- had a possible criminal investigation commenced against it,

- lost $22 billion in market value in the week following the Ethiopian Airlines’ crash in October,

- had more than 300 737 MAX 8s grounded worldwide,

- sustained significant reputational harm,

- received demands from airlines seeking compensation for lost revenue,

- been sued by crash victims’ families, and

- had sales orders cancelled or suspended.

This is a crisis from which it may be difficult to recover.

One could trace back some of the risks to its decades-long rivalry with Airbus and an effort to remain viable.

When American Airlines indicated it was close to finalizing an exclusive deal with Airbus for hundreds of new jets, Boeing sprung to action. The New York Times reported that Boeing employees then had to move at “roughly double the normal pace” to avoid losing “billions in lost sales and potentially thousands of jobs.”

An SRM program would have required an assessment of the business model and the associated risks, including competitors, long before the call from the CEO of American Airlines. The risks would have been prioritized and this information would have been factored into strategic plans that would have included responses to material risks.

During the scramble, Boeing mirrored Airbus’ operations and mounted larger engines in existing models.

The objective seemed straightforward: Make minimum changes to avoid the need for training in a simulator, decrease costs, and build the redesigned model quickly. But a risk was that mounting larger engines changed the aerodynamics in the aircraft, requiring a consequential need for new software, a Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) which was supposed to prevent stalling. Boeing’s view was that pilots did not need to be trained on the software and federal regulators agreed.

However, in an effective SRM program the C-Suite would have been advised that the strategic and life safety risks were material and that training for pilots was indeed necessary. In addition, all such risks would have been assessed to determine whether they could be used to obtain a competitive advantage.

For example, including vital safety features in the base cost of aircraft (as opposed to charging extra for them) and requiring a focus group of pilots with no financial relationship with Boeing to test the newly designed 737 MAX 8s and the MCAS system would have been a way to solidify Boeing’s reputation for safety first.

An SRM program, which monitors progress in achieving strategic objectives with a focus on continuous improvement, would have looked at the Indonesian Lion Air and the Ethiopian Airlines crashes as an opportunity to confirm that Boeing puts safety first by grounding the aircraft. Instead, Boeing urged the U.S. to keep flying its jets until after 42 regulators in other countries had grounded them and appeared to care more about economics than life safety. Only seven months ago, Boeing was synonymous with efficient jet planes and commercial aviation – it was a reputation that took decades to build. Now, the company has a long, uphill climb to resolve its many challenges and rebuild its brand.

An SRM program cannot succeed without full support from the C-Suite as it has to be integrated into the business model and decision-making processes in order to be effective, and in time we will learn more about what risk management protocols were followed across Boeing’s organization.

At RIMS 2019, Marian Cope will lead a panel of industry experts in discussing reasons to transform an ERM program into a SRM program or develop a SRM program in NextGen ERM: Strategic Risk Management. The session will take place April 29th at 1:30 pm.